DevOps in Salesforce - Failing to Plan is Planning to Fail

DevOps in Salesforce: Failing to Plan is Planning to Fail

Welcome to our second post in a series about building an effective Salesforce deployment pipeline that your whole team will love. If you missed the last post in the series where we introduced DevOps in Salesforce, check it out here.

Written by Aaron Allport and Stuart Grieve.

The need for an Salesforce environment strategy

Your environment strategy is important. Without one, how is it possible to know where someone is working? How are you going to ensure that what you have developed is tested in multiple, isolated environments with different contexts, such as systems integration and user acceptance testing; to ensure new functionality is production ready? How will developed artefacts move from one environment to the next? This information is necessary before any automation can be developed.

You may not know the answer to these questions right away, but that’s the point. Rather than assuming one size fits all, we believe deep-diving into a team’s distinct requirements is the most effective approach to outlining a strategy that’s tailored to the needs of your organisation.

Your process should require Development and User Acceptance Test (at a minimum), but you may also need to consider an Enterprise Service Bus (ESB). For example, MuleSoft can be employed to mediate between systems. You will, therefore, need to perform System Integration Testing. This would typically mandate the use of a Systems Integration Test (SIT) environment between Development and User Acceptance Test (UAT).

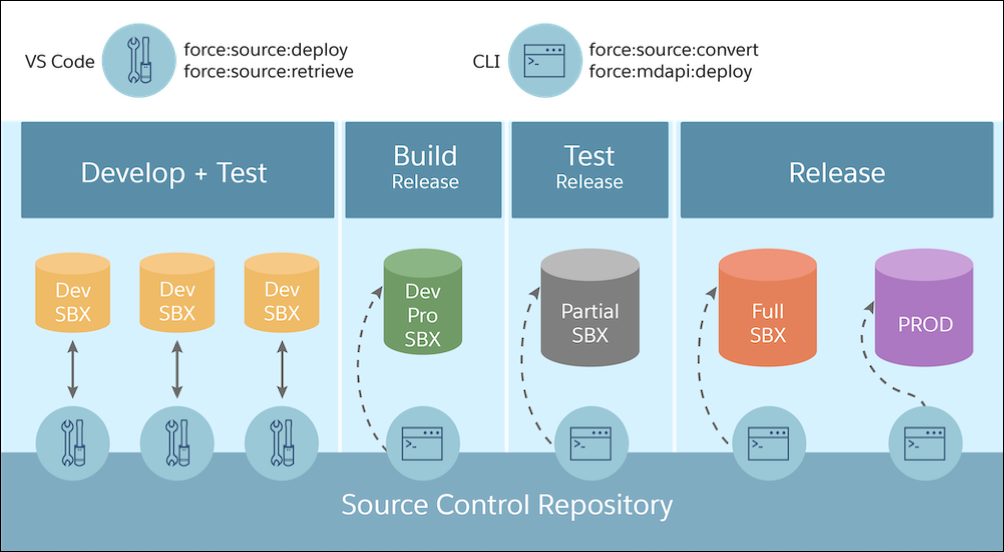

If your development process employs SalesforceDX, and scratch orgs in particular (more on that later), you’d also look to have a Development Consolidation (DEVCON) environment.

This could result in the following development and deployment flow:

Once your environment strategy has started to take shape, you should begin to assess the types of Salesforce instances (also called “orgs”), available to you. At a high level, there are three categories: Production, Development and Test. Whether you are a customer, implementation partner or ISV will determine which are relevant. For the most part, customer teams will focus on Production and Development only. In case you’re new to Salesforce, your Production org is the environment your users are utilising the functionality provided and accessing your business’s data. It’s also important to remember each environment differs in shape — there are four levels of Salesforce subscriptions. Let’s explore the environment estate in more detail.

The Development environment category can be complex, but it needn’t be. There are two types of Development environments: Sandbox and Developer Edition. A sandbox is a close representation of production, though may have different user licenses and data storage restrictions based on the variation (and there are a few). A developer edition org mirrors one of the production editions we mentioned earlier and is entirely free, however, again has much higher restrictions on licenses and storage. Both Sandbox and Developer Edition orgs are going to be where you build and test your functionality.

For further information on the differences between each environment take a look at the Introduction to Environments. From here, you can begin to identify the environment types to your strategy.

Developers love scratch orgs. Functional teams… may learn to

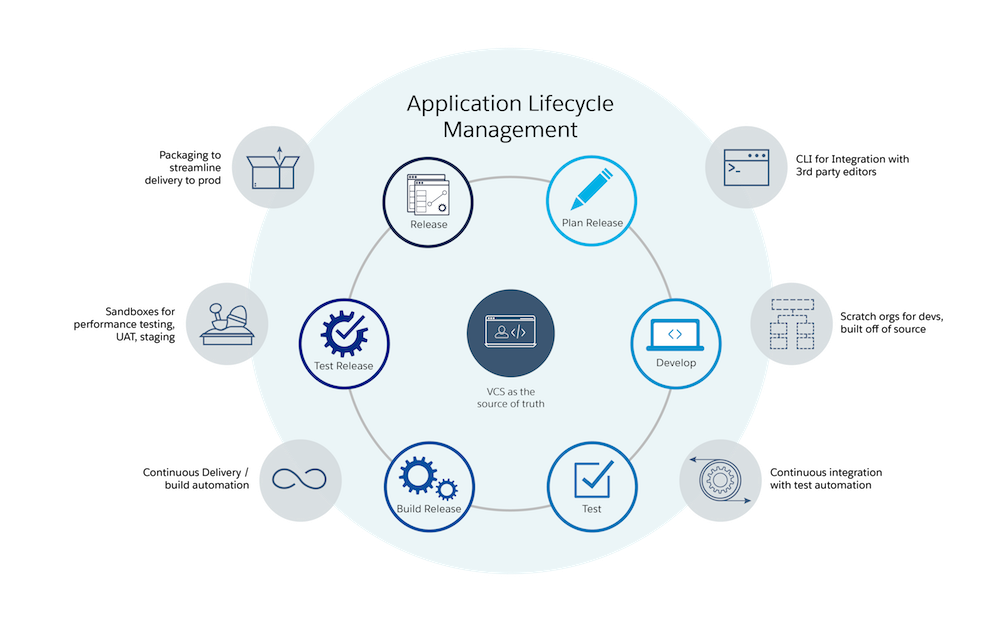

In the previous post, we discussed Infrastructure as Code and SFDX’s introduction of Scratch Orgs; but how do they fit into your environment strategy?

Developers love scratch orgs. Simply put, they allow a developer to spin up, on-demand, a Salesforce environment configured to a pre-defined and shared template. Within minutes, they’ll have code and metadata deployed to it; perhaps even some sample data. The developer is free to make this environment as unstable as they please and know their changes won’t impact the rest of the team. When finished, the environment can simply be torn down. These small, almost “single-use” environments are perfect for getting discrete pieces of functionality developed rapidly and tested outside of the team’s core environments.

Sounds perfect, right? Well, whilst developers enjoy scratch orgs and the benefits that come with them, functional teams often show a preference for developing metadata changes on a single shared sandbox.

It is entirely possible to utilise a combination of scratch orgs and a single shared sandbox across the development and functional teams. If your team is migrating from a deployment lifecycle primarily employing change sets, often the learning curve for functional teams to adopt new tooling is far steeper than for their technical counterparts. By no means should it be an all or nothing scenario, so take an iterative approach. Once your developers have cemented scratch orgs into their lifecycle, let them be the champions for any functional team members curious of the benefits.

In short, you may wish to utilise scratch orgs where appropriate for your team. If desired, functional teams can continue to use a shared sandbox as they will have done in previous projects, whilst learning the benefits of scratch orgs. Ultimately, we would advocate for the use of scratch orgs across functional and developer teams in the long term.

Who owns what?

An automated deployment pipeline, playing nicely with a well-defined environment strategy, means that no-one outside of the organisation admin(s) should have access to environments outside of the DEVCON environment. Gone are the days where developers have Production System Administrator access “just in case”, when in reality, they likely do not need it. With a consistent environment approach and deployment pipeline, automated tooling, and isolated testing, issues should and can be reproduced entirely in non-production contexts.

Developers and functional team members call the DEV/DEVCON space home. They should have read-only access to SIT for verification but little more. Access to configure or develop the SIT environment should be given to non-administrators in a read-only capacity only. Ideally, UAT would require even less access as the owners of Salesforce assume responsibility for the end-to-end environment.

In most cases, production access should be ad-hoc for absolutely critical issue investigation only. Arguably using a short-lived HOTFIX environment created from Production would be better suited for such investigation. This will enable producing and testing a fix on an environment which is on the production build; yet isolated from the production environment where business critical activities are taking place. Additionally, this environment doesn’t contain any future functionality currently in the development pipeline, making it an ideal candidate for hot-fixing production critical issues.

Automation is the key to consistency between environments

Nobody is perfect, and it is entirely possible for humans to make mistakes from time to time. Introducing automation into the development and deployment workflow reduces as much as possible the risk of human error. By scripting the deployment process and the nature in which code and metadata will make its way from one environment to the next, not only is the likelihood of error reduced significantly, but also time is saved by not having a person perform deployment tasks manually each time.

Modern tooling is designed for this scenario. For example, you can configure a release management tool to respond to changes on your repository and react accordingly. Pull Requests could be subject to a validation only; with merges then subject to a deployment in a target integration environment. Tokenisation of values can be done by having details of the target environment available in variables at run-time, and deployments and tests can be run by feeding variables into the parameters the SFDX commands expect in order to run. Execution timings can be determined as they’ll be consistent each time they run.

By keeping things as automated as possible, the actual process itself becomes part of your build. Who says you shouldn’t subject your tooling configuration to the same development and peer review process as the rest of the configuration, code and metadata for your implementation?

Things won’t just “go wrong” in future. The factors that influence what the automated processes do are subject to human mistakes (such as misspelling a username for an environment) but the process (invoking the command and authenticating to Salesforce) are not. Troubleshooting the deployment process just got easier!

In our next post in this series, we’ll look at the practical implementation of an automated Salesforce deployment pipeline, the associated tooling in this space and workflows to expect when putting in to practice the concepts we’ve outlined so far.